December 2002

Contents

The Seeds of Enmity

Richard Layton’s Discussion Group Report

In the October issue of The Utah Humanist we presented the chronological first half of the genesis of the present Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Here we are describing the last half, based on the discussion of the topic by David Schafer in the September-October, 2002, issue of The Humanist.

In 1920 The League of Nations bestowed on Great Britain a mandate to administrate Palestine and Transjordan (present-day Jordan). France was given a similar mandate over Syria and Lebanon. The British mandate, taking effect 3 1/2 years later, lasted a quarter of a century and left an indelible imprint upon the future course of events in the area. The League made preparation for self-government a principal goal of the mandates. The establishment of Britain as the ruling power inevitably led to increasing resentment by the Palestinians toward their new overlords. Up to World War I Britain had been primarily concerned in the Near East with maintaining its access to petroleum and other natural resources there, as well as control of sea and land routes to India and the Far East. Its policies in Palestine required attempting to balance the aspirations of the indigenous Arabs against those of ever-growing numbers of immigrant Jews, but this balance was never fully achieved. Arabs came to view Jewish immigration as a conspiracy between the British government and the Jews to create a colonialist Jewish state out of the whole of Palestine, excluding most Arabs.

Palestine’s Arab neighbors were angry about the situation, and various discords occurred among them. In general Arabs were hostile toward Zionist intrusions into “their” Palestine. With an eye to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s emphasis on self-determination, Colonel Edward Mandel House, his aide, wrote of the British plan for Palestine, “It is all bad and I told [Lord Alfred] Balfour so. They are making the [Middle East] a breeding place for future war.” David Ben-Gurion told leaders of the Yishuv (Jewish settlers), “…not everybody sees that there is no solution to this question. No solution!…We as a nation want this country to be ours; the Arabs, as a nation, want this country to be theirs.”

The Yishuv had some distinct advantages over the Arabs. The latter were disunited, comparatively uneducated, and unused to European thoughts styles of thought and organization. Many of the Jews had the benefits of European education and experience in various kinds of work.

Unprecedented rioting took place April 4-7, 1920 in which six Jews were killed and over 200 injured. The Zionists began to strengthen their militia, the Haganah. Renewed violence on May 1 claimed the lives of 47 Jews and 48 Arabs and wounded 146 Jews and 73 Arabs. British colonial secretary Winston Churchill sought to soothe Arab feelings by declaring that it was right that the scattered Jews should have a national center and home in Palestine. This would be good for the world, the Jews, the British Empire, and the Arabs in Palestine, since the Arabs could share in the benefits and progress of Zionism. He asked the Zionists to consider “the great alarm” the Arabs were feeling. The Jews organized the Herut Party, which later became the Likud.

Palestine enjoyed relative quiet, prosperity and development between the summers of 1921 and 1928,while Jewish immigration rates remained low. The quiet was broken September, 1928, in a dispute revolving around the Wailing Wall, the most sacred place in the world to Jews and the third most sacred place, after Mecca and Medina, to the Arabs. Within a week 133 Jews and 116 Arabs were killed and many more wounded. A British investigation concluded the Arabs had caused the violence, and trials condemned 25 Arabs to death. The British then issued a White Paper of 1930, intended to slow Jewish immigration. After pressure from the Zionists the White Paper was reversed. A deceptive calm fell over Palestine for several years. Both Jews and Arabs had learned they couldn’t depend on the British to defend them. With the rise of Adolph Hitler to power some Arab leaders welcomed the new regime and hoped for the extension of the fascist, antidemocratic governmental system to other countries. Secret Jihad societies arose, composed mostly of poor peasants. They conducted minor raids, killing a few Jews at a time. After a general strike in April, 1936, terrorism spread rapidly throughout the countryside. Britain brought in 20,000 soldiers and provided arms to Jewish settlements and 2.700 extra Jewish police. The Zionists became the soul of compromise and reasonableness. The Palestinians, confident of the righteousness of their cause and convinced that nothing but total victory for their side would do, pleaded the justice of their case in absolute terms, saying, “There is no compromise.” Repeated efforts by the British to settle the hostilities failed. Then the Jewish defense forces abandoned their “reasonableness” in favor of “aggressive defense” and counterterrorism, resorting for the first time to suicide bombings to kill Arab civilians.

The British used severe measures to suppress the rebellion, resulting in the Palestinians’ being worse off than they had ever been, becoming wards of the Arab states. A number of concerted attempts by the British during World War II to resolve the hostilities failed. Toward the end of the war, the Jews looked for an opportunity to resume their revolt against Britain. In February 1944, a Jewish terrorist organization, the Irgun, now led by Menachem Begin, began to blow up or attack British government buildings in Palestine; and another Jewish group, the Stern Gang, assassinated Lord Moyne, the British minister resident in the Middle East and a close friend of Prime Minister Churchill. Up until then the British had been promoting a policy of partitioning Palestine between the Jews and the Palestinians, but now Churchill withdrew support for that stance.

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt died in April, 1945. The British then ousted Churchill from the prime ministership in July. These two leadership changes made the United States much more receptive to Zionist claims and Britain much less. Britain wanted to avoid offending the Arab nations. It was fatigued and its empire on the verge of decline as its colonies asserted their desire for independence. “The United States, by contrast, was just beginning to feel like one of the world’s superpowers and thus only too happy to show the British how things should be done,” says Schafer.

After Germany’s surrender, the Irgun and the Stern Gang in effect resumed war against Britain when the British foreign minister, Ernest Bevin hinted he was going to follow a pro-Arab line. The United Nations set up a Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) of eleven neutral nations. The Committee recommended the termination of the British mandate and independence for Palestine after a transitional period. Seven states favored partition into an Arab state, a Jewish state and an international Jerusalem. Three favored an independent federal state, and one abstained. The Jews accepted the majority report but the Arabs threatened war if either report was accepted. In November, 1947, the General Assembly barely passed Resolution 181, allowing for partitioning Palestine into an Arab state of 4,500 square miles with about 800,000 Arabs and 20,000 Jews, and a Jewish state of 5,500 square miles with 538,000 Jews and 397,000 Arabs. In January, 1948, a volunteer “Arab liberation army,” mostly from Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, started to enter Palestine and secured some of its infrastructure. Then the Haganah came in and swiftly turned events around. After a particularly infamous massacre of an Arab village near Jerusalem and an Arab retaliation in kind, the Haganah took by force most of the territory allotted to the new Jewish state by Resolution 181.

On May 14,1948, the Union Jack was hauled down and the British mandate came to an end. David Ben-Gurion read the Proclamation of Independence, announcing the establishment of Israel, to the Yishuv. A new chapter had begun in the history of the Middle East–unfortunately with new hostilities initiated the very next day by Israel’s Arab neighbors.

Creed Trumps Deeds for BSA

The Boy Scouts of America (BSA) this week gave one of their top ranked Eagle Scouts an ultimatum: affirm a belief in a higher power or quit the Boy Scouts. “This is the kind of lesson the Boy Scout leadership is teaching young men: despite devotion to a cause, despite dedication to others, despite accomplished service, if supernatural beliefs differ, then loyalty is cast aside. Creed clearly trumps deed,” points out Tony Hileman, executive director of the American Humanist Association (AHA).

Darrel Lambert earned the rank of Eagle Scout after ten years of dedication to the organization and community. If Lambert followed BSA’s advice and professed belief in a supreme being, it would be a lie. “I wouldn’t be a good Scout then, would I?” he asked.

The Bedrock of Scouting Values, a BSA publication asserts, “Our commitment is that no child can develop to his/her fullest potential without a spiritual element.” Derek Sweetman, a Humanist Eagle Scout asks, “Why doesn’t performance alone prove worthiness? If the dedication and service is there, how is the person’s attitude toward religion relevant?”

“Lambert is a prime example that a failure to believe in God does not equate to a failure of good citizenship,” said Hileman.

The BSA is teaching youth to ignore accomplishments in favor of a declaration, sincere or not. By attempting to force a statement from Mr. Lambert the Boy Scouts of America are trivializing the meaning of belief. Hileman declared, “Its time for the BSA to live up to its own standards and end this practice of exclusion.”

Bush Signs Into Law US Subjugation To God

November 13, 2002: President Bush signed into law a bill reaffirming the reference in the Pledge of Allegiance to ours being one nation “under God.” Tony Hileman, executive director of the American Humanist Association(AHA) responded, “This legislation divides us when we need uniting, attacks the First Amendment when it needs bolstering, and places responsibility outside ourselves when we most need to accept it. “It is paradoxical that the words ‘under God’ and ‘indivisible’ are side by side in our nation’s Pledge of Allegiance. Our constitution intentionally had no reference to God because it’s not the job of the government to impose religious belief. How can a declaration of America’s subjugation to God unite the thirty million people in our country with no religious affiliation?

“Over recent months we’ve seen an overabundance of public religious endorsements by government officials. This latest action is just another swipe at Thomas Jefferson’s wall of separation between church and state. Our leaders forget that such separation is what maintains religious liberty and protects us from theocracy.” By placing our trust in a higher power we relinquish responsibility at a time when we are struggling with a war on terrorism and contemplating preemptive military action against another nation. Will Bush be relying on divine inspiration to guide his executive decisions as he places our citizens in harm’s way? I hope not.” Congress was overwhelmingly supportive of this latest legislation with only Barney Frank of Massachusetts, Michael Honda and Pete Stark of California, Jim McDermott of Washington, and Bobby Scott of Virginia voting against the measure.

Hileman concludes, “On behalf of the American Humanist Association, I commend these representatives who were brave enough to vote against this uncalled-for measure. AHA will continue to support those who speak out for religious liberty and freedom of conscience in defense of an indivisible nation.”

Americans For Religious Liberty

Americans for Religious Liberty (ARL) and the American Humanist Association are joining forces! The boards of both organizations have approved a plan whereby ARL becomes part of the AHA family.

ARL was founded in 1981 by Edward L. Ericson, former president of the American Ethical Union, and Sherwin T. Wine, founder of the Humanistic Judaism movement. Edd Doerr, currently president of the AHA, has been executive director of ARL since 1982. ARL’s mission is to defend freedom of religion and separation of church and state through research, publishing, litigation, and public speaking. This mission has meant strong support for religious neutrality in public education, defense of reproductive rights, and opposition to vouchers and other attempts to divert public funds to religious institutions.

ARL has published over 25 books, presented amicus curiae briefs to the U.S. Supreme Court and lower courts, engaged in direct litigations, and presented testimony to congressional committees. ARL also publishes the quarterly newsletter Voice of Reason. Both Edd and ARL Associate Director Al Menendez have spoken widely around the United States and appeared on radio and television and in the print media.

ARL will now be housed in the new AHA headquarters, the Mary and Lloyd Morain Humanist Center in Washington, D.C. “Both the ARL and the AHA will benefit from this new partnership,” said Edd. “ARL is not a Humanist organization itself but, rather, a broad-based organization that includes Humanists, Unitarian Universalists, Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and others who recognize the importance of the constitutional principle of separation of church and state.”

Uncle Sam’s Xmas ’02 Wish List

To Buy Me These New Toys for Christmas!!

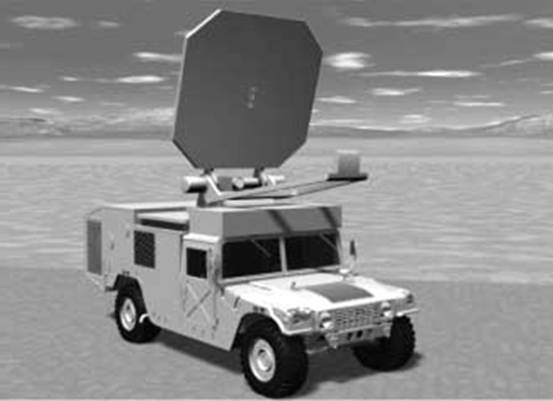

Pain Ray Microwave Device! Easily mounted on Hummer, great for subduing enemy civilians or even domestic dissidents! Goodbye, pesky protestors!

Bird of Prey from Boeing! Cool new stealth demo flyer for the “Death from Above” Crowd!

The ‘hit’ of this holiday season! As seen in Afghanistan. Our popular “Predator” Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, now with “Hellfire” Missles! Covert ops ready! In limited supply, so act now!

For all your domestic spying needs! The new Information Awareness Office, brought to you by Admiral John Poindexter, coupled with the new Homeland Security Office and Echelon, can monitor all communications, no matter how personal or private! Also, data mining, cryptography and more! A USA PATRIOT favorite! Not recommended for ACLU members.

Note: All prices are classified. Trust us, we’re the government.

Deluge Or Glaciation?

Flat earth or round? A crystal sphere around the earth as the heavens, or a cosmos filled with planets, stars, galaxies, and nebulas? An earth-centered planetary system, or a sun-centered solar system? An earth that is 6,000 years old, or an earth over 4.5 billion years old? Adam and Eve as the first humans, or a long hominid evolution? Evidence of a deluge or evidence of greater glaciations in the past?

In the past, whenever religion and science have been in conflict over some aspect of the nature of the physical world, the religious-I believe-have always been wrong. And when science has been shown to be in error, it has been scientists who have corrected the error, not someone “doing religion.” This is not to say that all scientists, past and present, are non-religious-quite the contrary. Most people, including scientists, have a religious belief. But I believe the really successful scientists are those who can keep their religious beliefs and their scientific endeavors separated. One good example was Austrian monk Gregor Mendel, who, by way of experiments in cross-pollination of garden peas and the careful statistical analysis of the results, gave us the basic tenets of genetics.

Sometimes new discoveries cause controversy, such as the well-known examples of Galileo and Darwin. Galileo was brought before the Inquisition for upholding the Copernican system, which put the sun in the center of our solar system, rather than the earth. Darwin’s studies and book Origin of Species established the theory of organic evolution and started the controversy about evolution that is still disputed by creationists today.

Another example is the biblical story of Noah and the flood. Most skeptics, including me, are unconvinced that it ever happened as presented in the bible. However, there is an interesting side story, involving the birth of glaciology. If you were to go back in time to around 1800, you would find that a fair number of scientists might be termed “religious scientists”. Coming from colleges and universities dominated and funded by various religions of the world and being religious individuals themselves, they approached science in a very different way than most modern scientists.

In the case of the biblical flood, these “religious scientists” set out to verify the flood by finding evidence to fit their beliefs. As they gazed upon the landscapes of northern Europe, they found what they were looking for: a rugged, seemingly chaotic topography, which was surely the work of the turbid waters of the flood. Their mistake, however, was setting out with their minds already made up, making the evidence fit pre-determined conclusions. This is not the scientific method.

In 1821, a Swiss engineer named J. Venetz presented lucid and organized arguments about the extent of past alpine glaciers. He argued that glaciers once extended much further down their pathways and that when they receded, they left behind large boulders, which were of the rock types from further up the path of the glacier. The glaciers also left behind poorly sorted surface materials and the U-shaped canyons. His arguments were not well received, as you may well expect. It wasn’t until 1837, when Louis Agassiz took up the argument, that this theory began to be accepted. Agassiz, along with a number of other associates, argued for years in favor of glaciers as the origin of the rugged topographical features observed in northern Europe. From those years of persistence and study came glaciology. To be fair, it should be noted that resistance to these new ideas did not only come from religious individuals but also from scientific orthodoxy (humans of all persuasions are stubborn to change).

The study of the historical origins of glaciology and the study of glaciers and their effects is a fascinating one. Suffice it to say that most geologists and other scientists interested in earth history accept glaciers as the origin of the features that were once considered evidence of the flood. They are now known as glacial moraines, till, erratics, eskers, and other well-studied and verified phenomenon.

Interestingly, a modern version of the “religious scientist” exists and is gaining momentum. One example is a television program called Origins, which presents varying aspects of what is called “creation science.” One episode sets forth the premise that the entire stratigraphic column was laid down in that one event, known as, you guessed it, Noah’s flood.

That’s right: all the rocks and sediments of the continents were laid out in differentiated layers, with igneous (volcanic) layers not mentioned. Thus, all the mountains are only as old as the flood (I presume), and the remains of living organisms became fossilized in the relatively short time since the flood. Having studied geology and physical geography, and having walked the trail from the North rim of the Grand Canyon to the Colorado River and observed the grandeur of the stratigraphic column as it really is, I find this particular “creation science” notion rather amusing, to say the least.

My intention is not to be anti-religious. I realize that faith in a deity brings great comfort to the majority of humans on earth. That faith, combined with human emotions, adds a richness to humanity, especially through the arts. But when the stubbornness of religious orthodoxy tries to hold on to mythological ideas about the physical world in the light of scientific fact they make a big mistake, and are often, if not always, in error. The religious faithful may get satisfaction from the mysteries that surround us, but for me, I prefer the ways of science: the ways of Agassiz, Galileo, Kepler, Newton, Einstein, Pasteur, Darwin, Faraday, Maxwell, Edison, Marconi, Bell, Fleming, Heisenberg, Harvey, Rutherford, Mendel, Planck, Lister, Jenner, Roentgen, Fermi, Bronowski, Hubble, Asimov, Gould, Sagan, Feynman, Dawkins, and many more. These scientists and hundreds more like them were not just awed by the mysteries around them, but allowed these curiosities to pique their interest, leading to experimentation, observation, testing, and coming up with answers, which have solved many a mystery before going on to the next. Again, the scientific method proves itself superior to the ways of religious science.

A quote from author Douglas Walton seems appropriate to end with: “The rise of science brought with it a kind of positivist way of thinking, to the effect that knowledge should be based on scientific experimentation and mathematical calculation, and that all else is subjective.”

–Robert Lane

Changing Utah Values

Governor Mike Leavitt refused to sign a proclamation declaring “World Population Awareness Week,” citing zero population growth as not being consistent with Utah values (Rolly & Wells, Oct. 21). “Not consistent with Utah values.”

Hmmm, I have seen Utah values change based on social pressures in my lifetime. I remember when the civil rights movement threatened the LDS Church. There was a great deal of public discussion, some called it prayer, among the majority.

I encourage my LDS friends and neighbors to join the rest of us in discussions about the growing population problems. Fewer people means more water, smaller-sized classes in our public schools, less need for more highways and a generally higher availability of so called scarce resources. Let’s give our grandchildren and their children a comfortable, peaceful place to live.

–Wayne Wilson

This Letter to the Editor was published in The Salt Lake Tribune on November 2, 2002

Humanism: A Joyous View

You may be among the thousands who do not realize they are humanists. If this is so, you may be missing out on a great deal. Your search for meaning in life which is in harmony with your intelligence can be over. You can have a thoroughly consistent basis for meaning, moral values, and inspiration.

Humanism, an alternative to religious faith, can fulfill many of today’s desires and needs. It is in tune with the revolutionary growing knowledge of our physical and mental worlds. It reinforces positive aspects of rational thinking and feeling, and now when some old ideas no longer seem relevant it may provide an alternative source of joy and strength. Rational thinking and its handmaiden science free one from the guilt brought about by giving lip service to ideas which are not actually believed. We no longer find ourselves existing in a waiting room to enter heaven or hell. Humanism encourages service to others and offers the sense of community and connectedness with others.

–Lloyd and Mary Morain

Reflections on Being Tried for Murder

I have recently had the misfortune of being tried for the “untimely deaths” of five of my patients, not just once but twice. In each of the two trials I learned a great deal about the judicial system, some of it positive and illuminating, and some of it quite distasteful. It was certainly positive to finally have my innocence vindicated, but unfortunate to have spent every last cent and then six months in prison.

The first trial lasted five and a half weeks. The prosecution tediously presented volumes of trivial detail and irrelevant minutia that not only confused the jury but also left them bored to distraction. This first jury refused to convict me of the charge of first degree murder, as requested by the state lawyers, but compromised with a verdict of guilty on three counts of negligent homicide and two of manslaughter, leading to a sentence of fifteen years. The second trial of three weeks was conducted in a much more expeditious way; the defense witnesses were knowledgeable and informative in their testimonies, while the state witnesses were a bit more circumspect than the last time. The jury quickly acquitted me of all charges.

Prior to my arrest none of the patients’ families had filed a complaint with the hospital, state agencies, or the medical societies, nor apparently had any even met with a lawyer. I can only imagine the scenario, but there came a day when a state investigator knocked on the door of each family to announce that their loved ones had not died natural deaths but had been murdered. One can imagine the rush of emotions that each of these individuals must have felt, running from fear, to guilt, anger, and pain. The loss of the departed had already been grieved, the dead had been buried, and the pain had been accepted and resolved. Then the prosecutors arrived to exhume the bodies. The survivors were now given a new and grisly burden to bear. The exhumations raised again the grief of their loss, not this second time to be so properly borne, endured, and buried.

As I sat in court each day listening carefully to the ebb and flow, the whole significance of our system of trial by jury became clear to me. I watched the families of the alleged victims sit through every pretrial hearing and both courtroom trials, waiting impatiently for the justice they felt they deserved. I was dismayed that they had become so righteously indignant over care I had provided and believed was appropriate and ethical. I now listened with the hope that after these family members had heard the facts and the expert explanations, they would feel relieved. I hoped they would find some peace when they learned that their decision had been a rational and wise one: to have me withdraw aggressive medical interventions from their dying, demented loved one and to replace that with compassionate comfort care.

It is now clear that the second jury did indeed hear the message. Justice was done, although at great expense to the state. The parade of experts provided a thorough explanation for those family members who were open to hearing it. This opportunity to hear a full disclosure of all the relevant facts is the true intent and meaning of justice, so that those who continue to harbor inner conflicts or ill will may be able to reach closure.

Among those less well informed I have no doubt that many questions, suspicious, and unresolved issues remain, many of which I believe arise from our widespread ignorance about the process of dying. Our society has essentially denied the reality of death. Most people have very little contact with death, and with our prolonged life expectancies we are not touched by it as closely or frequently as were people only a generation or two past.

A Latin term used in Medicine, in extremis, denotes not simply a state beyond which nothing further can be done to save life; it describes a process through which the body passes as it prepares to shut itself down, permanently: The process of dying.

Lewis Thomas in his book Medusa and the Snail has a chapter entitled, “On Natural Death,” which contains ideas so important to this subject it should be included in every pamphlet provided by hospice services. Thomas describes a process that takes place in the mouse at the instant it is caught by a cat. He writes,

“…peptide hormones are released by cells in the hypothalamus and the

pituitary gland; instantly these substances, called endorphins…[exert]

the pharmacological properties of opium; there is no pain.”

He ends with,

“Pain is useful for avoidance, for getting away when there’s time

to get away, but when it is endgame, and no way back, pain is

likely to be turned off, and the mechanisms for this are wonderfully

precise and quick. If I had to design an ecosystem in which creatures

had to live off each other and in which dying was an indispensable

part of living, I could not think of a better way to manage.”

Thomas then quotes the 16th century French philosopher Montaigne, who had had a near death experience which led him to write,

“If you know not how to die, never trouble yourself; Nature will

in a moment fully and sufficiently instruct you; she will exactly

do that business for you; take you no care for it.”

It should certainly serve to support the faith of those who believe in a merciful Creator to know that with all the violence built into the law of the jungle, prey are provided with this mechanism to guarantee a gentle and merciful demise. And this mechanism is fully active in humans.

During my second trial some experts discussed the notion of delirium, which is commonly seen in the demented. Since the five patients who died under my care were all in advanced stages of dementia, there was also substantial testimony about both the nature of dementia and the meaning of delirium. Dementia, a disease condition of the brain, results in destruction of large amounts of brain matter, leaving the afflicted individual trapped inside a tangle of non-functioning brain structure. In the later stages of dementia the process also leads to a general wasting of the entire body, eventually and inevitable leading to death. It is not in any way the same as psychiatric diseases such as phobia or neurosis, which are conditions of the mind, not the brain.

Delirium is rather difficult to define, but it is an altered state of mind that may incorporate hallucinations or other reality distortions, frequently associated with wild swings in brain activity. Delirium can be either pleasant or tragic. The endorphins provide a kind of quiet, pleasant delirium, but dementia can result in a delirium that is frenzied and destructive. The experienced caregiver knows it when she sees it, just as the knowledgeable caregiver can recognize the dying process when she sees it.

The demented individual presents many difficult problems for the caregiver, but one of the most perplexing is the inability of the demented to be able to identify and describe physical pain. The destroyed brain not only does not allow effective communication, it frequently does not even give the demented patient a correct interpretation of the problem, so they may not even recognize that they are in pain. Such patients may exhibit agitation or bizarre behavior in their response to unrecognized, painful stimuli. Since we have no blood test or “pain-o-meter” to measure the symptom of pain, we can sometimes only ascertain this by giving an opioid to see if the patient’s behavior improves.

In the normal, natural death, passing is made gentle and pleasant by the brain’s release of its own natural endorphins. Although we know of the severe pain many cancer patients suffer, once the dying process begins their pain is often relieved. In many of the demented, however, there appears to be the worst of all possible worlds; the brain seems to be both unable to discern the pain and unable to release nature’s merciful endorphins. This necessitates the administering of powerful pain relievers in generous dosage to help nature do what the disease process has forestalled, if one is to be as kind as we have seen nature to be when death is natural.

Our country is currently experiencing something just short of a war occurring between the regulatory agencies and those physicians responsible for compassionate pain treatment. The knowledge gained just in the past ten years about the proper use of opioids has been significant, and the new knowledge suggests that much of our past use of opioids has been meager and stinting. Now that bureaucrats, middle managers and lawyers have an ever increasing involvement in the way health care is delivered, innovative modalities and changing treatment practices are challenged almost everywhere, as one might expect. Perhaps the successful outcome in State v. Weitzel will help to further assertive and compassionate palliative care; I hope so.

I am very happy that I have been acquitted and that I may once again look forward to regaining my livelihood and respectability, but my greatest happiness comes from knowing that a jury of laypersons can and did hear the message; they saw the bigger picture. Although all my own assets have been spent, as well as considerable funds provided by donors, I still feel my optimism has been redeemed, and I am hopeful for my own future as well as that of conscientious and compassionate physicians everywhere, and most important, the patients we serve.

–Robert Weitzel MD

Point – Counter Point

Tom Goldsmith, pastor of the First Unitarian Church in Salt Lake City presented a sermon entitled The Limits of Humanism on October 27, 2002. Hugh Gillilan, a former pastor in the same pulpit, and also a chapter member of Humanists of Utah gave a rebuttal he called Still Thankful for Humanism in Our Tradition on December 1, 2002. Click the links below to see the full text of both sermons.

Text of a sermon offered to the First Unitarian Church in Salt Lake City

Limits of Humanism

I just got back from meeting with my study group in Boston, a loosely configured band of 18 UU ministers who have been meeting for 22 years. Originally we were all Boston based, but over time our church settlements have spread us throughout the country. Nonetheless, most of us make it back to Mecca and I especially enjoy breathing the air of Unitarian dominance. I understand, however, that no effort will be made by Boston Unitarians to purchase Beacon Street, now or in the future.

During one of our happy hour occasions, we reminisced about mistakes we have made in the ministry, which we surely would never make again. We seemed to center on memorial services, and all that could possibly go wrong. One dear colleague of mine shared the story from the earlier years of his ministry when a woman from his congregation died unexpectedly. She was very well liked, admired, and her death was a jolt to everyone. I believe her name was Nancy.

Nancy’s sister from California whom nobody knew, came out for the service and asked the minister if she could say a few words. He of course agreed. His mistake, however, was in failing to warn the congregation that Nancy’s sister was an identical twin. He has never heard a congregation gasp and shriek like that ever again. Their entire theological underpinnings came unglued.

Death and the possibility of an afterlife – let alone a resurrection, which about 200 Unitarians thought, they witnessed during that memorial service – lies pretty much at the heart of a person’s theology. We all ask: Is there really some special place other than this world to which we may go after death? Many religions have myths that speak this way. It’s quite a dualistic system whereby this present world and an entirely “other” reality somehow co-exist. The other reality may be a place where we go when we die, and it also somehow represents cosmic head quarters that sends communications down to this world from above. And in turn, we mortals pray that our requests of those who inhabit the heavens are heard clearly and compassionately.

In this particular cosmic scheme humanity has really no power of any significance. In fact, all human responsibility is undermined by this dualism because truth and authority dwell in another realm. We’re pretty helpless, or at least humbled by our powerlessness.

In traditional Christian thought, God is conceived largely as a personal agent. That is, the point of reference is based on the model of a human person. God is thought of and referred to as a king, or lord… as father, as a Being who judges and speaks and acts and loves and hates and rules and creates all and who will ultimately bring all to its end.

The tendency to frame God in our likeness and to understand God as a concrete reality existing in some identifiable form is increasingly difficult to defend. Human beings have progressed greatly in their understanding of the world and the universe to the point where contemporary thinking clashes significantly with traditional views. A very simple example of a radical shift in human intellectual development reveals grave doubts that we ever entered into a covenant with God. We tend now to dismiss a special relationship between God and Humanity, one that was never realized between God and other creatures. Now that we have grown so very conscious of the ecological interdependence and interconnection of all of life, we see an exclusive relationship between God and us as highly problematical.

A Christian theology professor of mine, (from way back), Gordon Kaufman, questioned whether ‘Christian God-talk” can even continue to be regarded as intelligible. I believe he would take the position similar to Paul Tillich who emphasized that “God does not exist.” That is, God as a particular being does not exist but that God should be thought of simply as “being-itself.” “The Ground of Being” is the phrase that Tillich popularized. The Power of Being.” The modern mind can’t help but resist the concept of God as an object, or a concrete reality out there. If space exploration has taught us anything it’s that there is no such concept as “out there.” There’s no up or down in the universe.

The Humanist movement, originating in the early 20th century, embodied a philosophical pragmatism that reinforced the premise that a dualism between creator and created just didn’t compute. And by rejecting God, Lord, Father, other worldly being, a new religious orientation developed making traditional faith highly suspect.

But Humanism actually contributed more to religious conversation than just negating God. By eliminating an anthropomorphic God, Humanism stirred the pot by proclaiming that the future of the world rested in human hands. That is to say, we are not helpless after all, and we need to make the world a better place because our fate is not left up for grabs, to be determined by an angry or judgmental God. Humanity has the power to save itself, save the earth, and we had better not squander this gift of life by our propensity for greed and war and intolerance.

The formal beginnings of Humanism lie within Unitarianism. Perhaps the first Unitarian to use the word “Humanism” was Frank Doan, in 1908. He was a professor of psychology and philosophy of religion at Meadville Theological School. He had great influence over young Unitarian minds, and several of Doan’s students were signers of the Humanist Manifesto in 1933. (1) The big Unitarian names often associated with launching Humanism more formally in a religious context were John Dietrich and Curtis Reese, who in their meeting in 1917 discovered that they had compiled a similar volume of Humanist sermons. The Humanist disdain for traditional theology and language began making significant inroads in Unitarian churches, especially in the west.

In 1937, Frederick May Eliot was elected president of the American Unitarian Association. He is part of the Eliot family who founded our church in Salt Lake City, a nephew I believe, but his election proved quite a turning point for our denomination. Eliot, not really a flag waving Humanist himself, but rightfully considered an ally of the Humanist movement, raised the anxiety of New England theists when he ran for president. Don’t forget that the Unitarian establishment in Boston even at that time, consisted mainly of liberal Christians, but Christian theists nevertheless. They may not have been Trinitarians, but their theism did produce hymns and liturgy that offered all the trappings of mainline Protestantism. (I have the old hymnbooks from that era in my office, and -with your permission – we may want to do a traditional Unitarian service from say…1930. That might be a good Sunday for you to bring your conservative friends to church).

At any rate, the nervous theists felt obliged to challenge Frederick May Eliot and nominated their own candidate, a Rev. Joy. But just before the election there was so much fear of yet another theological controversy within Unitarianism that Joy withdrew and Eliot ran unopposed – similar to Saddam Hussein’s sweeping victory last week in Iraq. But the point is, Unitarianism and Humanism were now somehow fused at the hip.

Humanism obviously did not evolve out of thin air. There existed a climate or a liberal impulse that made Humanism possible. Let me briefly summarize just some of the milestone publications that (in my opinion) served as building blocks for Humanism.

Back in 1835 when Transcendentalists challenged the corpse cold Unitarianism in Boston, a German theologian named David Strauss wrote “The Life of Jesus.” The book offered (perhaps) the first wave of good biblical criticism where he stated that the bible needed to be scrutinized with the same requirements of consistency, accuracy and supportive evidence as are reserved for any historical document. And in doing so, he concluded, we were left with no option than to view the miracles of Jesus as symbolic.

Another German, the philosopher Ludwig Fuerbach wrote “The Essence of Christianity” in 1855. Fuerbach challenged the conventional views of religion in that he attempted to understand divinity as a projection of human needs, desires, and fears. In other words, he formulated the old cliché: God is made in man’s image not man in God’s image.

Moving ahead to the turn of the century, just as Humanism was being formulated, Sigmund Freud explodes onto the scene with “The Future of an Illusion.” God, as Freud maintained, serves merely as a projection of human fears and wishes.

Humanism gives us much to be grateful for, namely a clear departure from a judgmental God who fills us with fear and guilt. Humanism brought science and reason to the religious table. Humanism shook all the superstition out of religion and forced us to look squarely at the world with humans as responsible for charting the future course.

This church in Salt Lake was served by one of the greatest Humanist ministers of the 20th century. Ed Wilson, a signer of the Humanist manifesto and editor of the Humanist Press Association, ministered here from 1946-1949. Ed was raised a Unitarian in Concord, MA, but that church shaped him into a fine theist. While at first he thought of a career in business, he went instead to Meadville Theological School to become a Unitarian minister. Meadville, as you’ll recall, was influenced greatly by professor Frank Doan, the Humanist. And the last words Ed heard from his family as he embarked by train to Meadville was “Don’t let those Humanists take away your faith.” (2)

It was on the train, however, not at Meadville, that Ed had a conversion experience. He sat next to a philosophy professor who upon learning that Ed was headed to seminary, told him that it was a shame that such a bright young man would throw away his life for a profession grounded on such false premises. By the time Ed got off the train, he had converted to Humanism and was hungry for the Humanist teaching he would receive at Meadville.

Ed finished his life at Friendship Manor, and he was a wonderful support to me, and also a personal friend. Thus it’s with some trepidation that I dare speak this morning to the limits of Humanism. Ed’s ghost may still lurk in this chapel, and this church has (historically) been very committed to Humanism. I once owned an American Humanist membership card myself, and although I would never burn it, I have put it aside.

Humanism was right when it declared that religion need not involve a relationship with the supernatural to be justified, but Humanism simply substitutes scientific truth for the old religious truth. Whether the truth you seek to order the universe comes by way of God’s revelation or the laboratory, the same kind of desire exists to find certainty in a terrifying world.

Religion for me must deal with life and death and all its inherent problems, difficulties, and anxieties. The very human needs that religion must address gave birth to Christianity, for example. Early Christians had no need for a miracle based religion among the Jews, but the profound need to address those same fundamental human issues that still confront us today. For the early Jewish Christians, Jesus was a prophet who called God, “Abba” or father. It was a way to connect personally with the frightening elements in the universe because people felt alienated and alone…unbelievably alone in the vastness of it all.

Jesus’ suffering gave them meaning in that they no longer suffered alone. And when Jesus asked, “Why hast thou forsaken me?” the Jewish Christians no longer felt isolated and abandoned themselves. Because in life, even today with all the science at our disposal, we feel abandoned in our suffering and just alone in the universe. Religion must address how we live and how we die. Forrest Church, my Unitarian Colleague and friend from New York, defines religion as “our human response to the dual reality of being alive and having to die.” Knowing that we are going to die we question what life means.

For me, the Humanist “statement of truth” however grounded in scientific inquiry, offers little to quench the thirst for a deeper understanding of what life means. Or, as the Buddha might put it – “What is useful to bring the fullness of life to human beings?” The Buddha says, “I have taught a doctrine similar to a raft. It is for crossing over to the other side, not something to be grasped or clung to.” (3)

And Jesus’ ministry, understood in so many different ways, always comes back to figuring out what is meant by “an abundant life.”

Empirical evidence, one of the hallmarks of Humanism, seems poorly suited in dealing with these dynamic human concerns about meaning, bringing fullness to life, and discerning an abundant life. Humanism debunks supernatural orders, which I appreciate – I think we all do – but even in that generation that followed the early Humanists like Reese and Dietrich, we have the likes of Eustace Haydon who said: “Through science man will become master of the earth and rise to undreamed heights. Science will release the potentialities of every soul in the new world, and the production of sick souls will no longer be possible. Purpose will be given to life. The old tragedies, the ancient evils, will pass away.” (4) I have not heard Humanism offer much different in the last 60 years.

Old tragedies and ancient evils have not passed away, and I doubt they ever will. It seems to me that Humanism either ignores or stoically endures hardships. There is no room in Humanism’s sunny disposition and its teaching of human progress forever upward and onward, for evil, suffering, and tragedy.

I want to introduce a new term, which frightens Humanists and many Unitarians as well. The word is “mystery,” and it smacks of other words like “unclear,” or “obscure,” denoting some distant object (possibly God), which we cannot quite discern. Mystery is unfortunately associated with the notion of God or some transcendent reality enveloped in a fog that can’t be scientifically proven, and thus rendered inconsequential.

But the theologian, Karl Rahner, gives “mystery” a totally different understanding that I find helpful. Life itself confronts us as mystery. “Mystery” say Rahner, “is something with which we are always familiar. In the ultimate depth of our being we know nothing more surely than that our knowledge, that is, what is called knowledge in everyday parlance, is only a small island in a vast sea that has not been traveled. It is a floating island, and it might be more familiar to us than the sea, but ultimately it is borne by the sea. Hence the deepest question for us humans is this: which do we love more, the small island of our so-called knowledge or the sea of infinite mystery?”(5)

This crucial question prompts me to consider that Humanism remains confined to the small island of our so-called knowledge rather than admit – let alone love – the sense of infinite mystery.

Mystery, then, does not refer to a direct perceptual experience of something like darkness or dense fog. Instead, mystery is an intellectual term rather than an experiential one. When we explore whether life has meaning or why anything exists, we are (to be honest) baffled. We’re dealing with questions, concerns, issues, that exceed what our minds can handle.

I try to be comfortable (not always easy), acknowledging the mystery of existence. I am prepared to leave the tiny island of empirical evidence and embrace the infinite sea of mystery – a dimension that surpasses the very limits of my intellectual capacity.

When I confront loneliness and suffering and tragedy…

When I confront the puzzles and conundrums of life’s meaning and death’s meaning…

I am dealing with the very stuff of religion.

Life is more than the sum of its parts. It’s not just about understanding the physical, biological and historical processes. It’s more in line with “what brings about life’s fullness? How do we live abundantly? Or as Thoreau put it, how, at our deathbed do we avoid feeling we were never alive?”

It is mystery that nourishes the very center of our lives. The small island of our so-called knowledge provides us perhaps with a bit of certainty that we crave. But it is the infinite sea of mystery, that which baffles and befuddles, that ultimately engages our hearts and our passions in the business of religion. Answers will always be illusive, but the adventure in the sea of mystery, the continual search for some illumination fuels our religious sensibilities and keeps us fully engaged in trying to plumb life’s meaning as we breathe, love, exist…while always in the shadow of death.

Humanism has helped us think critically, and underscores the virtue of rational thought. Humanism is limited from my experience in that it refuses to honor the mystery in which the real fullness of our lives must be explored.

Footnotes

- Schulz, William Making the Manifesto: The Birth of Religious Humanism Skinner House p.19

- Ibid p.106

- Kaufman, Gordon God, Mystery, Diversity: Christian Theology In a Pluralistic World Fortress Press p.192

- Schulz, William Ibid p. 43

- Foundations of Christian Faith Seabury Press p.22

Still Thankful for Humanism in Our Tradition

The following sermon was given to the First Unitarian Church in response to Tom Goldsmith’s sermon a few weeks earlier

Late last summer our family gathered for a reunion at an idyllic campground in Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton Forest. On one of the camping nights I found myself awake about 3:00 AM. All was delightfully peaceful, a mountain stream was rippling nearby and in the distance a Great Horned Owl was calling its mournful cry–which some bird commentators have said sounds like, “Who’s awake? Me too”. As sometimes happens in such wakeful circumstances my mind was flitting from subject to subject and I began thinking about what I might discuss on this occasion. Tom, in his typical efficiency, had asked me earlier in the summer whether I would consider speaking on this fall date, and so I was ruminating that night on what was really meaningful to me and hopefully worthy of your time as well. My nocturnal conclusion was that I wanted to discuss humanism and my title would be, “Thankful for Humanism In Our Tradition”, because I really am very thankful for the humanistic philosophy that has vitally enriched our Unitarian Universalist history down through the decades to the present. So after returning to the city and in the weeks that followed I began gathering my thoughts when the unexpected occurred. Lo and behold, in late October Tom chose to deliver a thoughtful sermon on humanism and what he deemed to be its limitations. At that point I decided to change my title slightly “to Still Thankful for Humanism In Our Tradition”, and what I would like to share with you in our next few minutes together is a somewhat different perspective on humanism in our religious movement.

But first let’s turn back the clock a bit, quite a ways back as a matter of fact to the spring of 1952. I was a freshman at Ohio University and a student in Dr. Horace Houff’s Life’s Meaning and Morals philosophy class. On one memorable occasion Dr. Houff invited into our classroom a guest speaker from Yellow Springs, Ohio, who was the Executive Director of the American Humanist Association. The gentleman in question proceeded to discuss the philosophy of humanism. He was quite emphatic that persons could live decidedly moral lives without believing in a personal God. I have to tell you I was aghast at such heresy. I regarded myself a committed Christian, I was very active in Wesley Foundation, the Methodist student group on campus, and I prayed daily and diligently about numerous matters large and small –probably including forthcoming tests. I was also embarked upon preparation for the Methodist ministry at a Methodist seminary after completion of my college work . Morality without God! How could it be conceived?

Just nine years after that humanist presentation at Ohio University, in the summer of 1961, I candidated in this church and was invited to become the minister of this religious community. I came with great enthusiasm as an ardent humanist, and I relished the fact that this church had an illustrious history of humanist ministers preceding me including Jacob Trapp, Ed Wilson, Raymond Cope, and Harold Scott. Clearly, then, some radical changes had taken place in my philosophy and religious life between 1952 and 1961.

To quickly summarize those catalytic years:

A liberal arts degree at Ohio University did what a liberal education is supposed to do. I was introduced to the world. Philosophy, psychology, history, science, world religions, my English major and even ROTC all opened up vast new intellectual horizons as the world came flooding into my psyche. And in that very same psyche were also subterranean doubts that had a disconcerting way of rising to the surface on occasion to trouble my Christian aspirations. I well remember a visit to campus by a Methodist bishop, and believe me, bishops in the Methodist tradition have considerably more power and august authority than bishops here in Zion –whether deserved or not. This particular bishop made himself available for counseling sessions and I responded to his offer and with him tried to sort out some troubling religious questions. I found his counsel similar to but no more helpful than my mother’s response years earlier when as a young boy I asked her how one could go on living after death when one’s brain died. Both she and the bishop essentially said, “Son, you have to have faith.”

None the less, still enjoying Methodist associations and setting doubts aside, following college I went off to Garrett Biblical Institute in Evanston, Illinois, a graduate school decidedly more progressive than its fundamentalist sounding name would imply. There I thrived in pastoral psychology and counseling classes where for the first time I could delve into the provocative writings of such diverse personality theorists as Sigmund Freud and Carl Rogers. In Old and New Testament classes I was

introduced to more sophisticated methods of evaluating biblical writings, a process called “higher criticism”. Philosophy of religion classes offered new intellectual tools to evaluate religious tenets and traditions. Sociology of religion classes brought an inspirational awareness of noted proponents of the Social Gospel, men like Walter Rauschenbusch and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who insisted that the Christian Gospel must come to fruition in activities to promote social justice, world peace and the greater welfare of all the world’s inhabitants. I was privileged to hear Dr.King address a large crowd when he visited the nearby Northwestern campus. I remember well his stirring call for freedom for all persons without regard for race, color or creed, a theme familiar to all of us now via his “I Have a Dream” speech delivered in Washington, D.C.

Where I did not thrive in my seminary education was in the theology classes. One professor in particular was enamored with neo-orthodox theologians such as Reinhold Niehbur and Karl Barth, and he relished quoting the early church father, Tertullian, who reportedly said, “I believe because it is absurd”. Amazing! This learned professor also liked to quote other church fathers who declared reason to be the whore of religion leading believers down false paths. That’s w-h-o-r-e, but I think he could just as easily have said, reason as the horror, h-o-r-r-o-r, of religion. I’m here to tell you that during some of those theology classes I found far greater satisfaction and inspiration outdoors exploring the nearby gardens and wooded areas along Lake Michigan with binoculars in hand, especially during spring migration when the air was filled with beautiful warblers and other avian migrants.

And then a pivotal event occurred in my graduate education at Garrett. In a religious education class we were given an assignment to compare the religious education curriculum of the Methodist Church with that of another denomination of our choosing. I picked the Unitarian curriculum for my comparison and eureka! In that assigned task I encountered for the first time the writings of Sophia Fahs, a central figure in creating Unitarian religious education materials of that day, and her delightful book, Today’s Children and Yesterday’s Heritage, as well as another volume, The Church Across the Street , which actually suggested that it was important to understand what other churches believed as well as one’s own. As I read these books and other Unitarian curriculum items I realized that here were religious education materials I could wholeheartedly believe in and covet for my own children. I knew then that I had to find out more about the hitherto unfamiliar Unitarian tradition which I proceeded to do.

There was another concurrent and crucial process going on in my life during my seminary days. To work on some personal issues I entered into psychotherapy with a psychoanalyst in the community, and among the many benefits of that process I gained the courage to look resolutely at some of the religious doubts that had nagged at me throughout my earlier life. I gained an increased confidence in my own perceptions, thoughts and intuition and a concomitant decreasing certainty in my previous Christian beliefs.

And yet, upon graduation from seminary I resolved to try to function as a liberal Methodist minister since I had enjoyed many rich experiences and associations in that tradition as well as a first rate graduate education, theology classes not withstanding. But that noble experiment only lasted two years. Intellectual integrity and increasing frustration caught up with me and on Ash Wednesday of 1961, at the beginning of the Lenten season with its intensification of Christian thought and practice, I mailed my ministerial credentials to my Methodist bishop, relinquished my position as the associate minister in the large Methodist church which I had been serving, and as I have noted on other occasions, I gave up the Methodist Church for Lent… and thereafter. After five interesting, challenging and economically vulnerable months that followed I had the privilege of becoming the minister of this church.

I might add that during those two Methodist ministerial years I discovered Julian Huxley’s very helpful book, Religion Without Revelation, which is still a classic presentation of humanist thought. I also had delightful conversations with David Pohl, then the Unitarian minister at Shaker Heights, Ohio, and Janet and I visited when we could the West Shore Unitarian church in Rocky River, Ohio, where Peter Sampson was a very effective minister. In addition I found welcome inspiration and enlightenment through the sermons of various Unitarian ministers distributed by the Church of the Larger Fellowship, then a correspondence church for Unitarians who were scattered around the globe.

With that prologue I would like now to offer some reactions to Tom’s sermon on humanism which he delivered last October.

I was very pleased when Tom paid high tribute to Ed Wilson, the minister of this church from 1946 to 1949 and a very forceful and tireless promoter of humanism within Unitarianism and Universalism as well as outside of those traditions. When Ed left the ministry of this church he moved to Yellow Springs, Ohio, to become the Executive Director of the American Humanist Association, and yes, Ed was the one who thoroughly rattled my cage in that philosophy class at Ohio University in 1952. He and I had occasion to chuckle over that coincidence in later years. I was decidedly pleased when Ed invited me along with numerous others to be a signer of the Second Humanist Manifesto published in 1973. Ed was also a prime promoter and signer of the original Humanist Manifesto in 1933 and for many years he was the editor of The Humanist magazine including during the time of his ministry here in Salt Lake City. Lorille Miller and Stan Larson note in their history of this church that Ed received an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from Meadville Theological School in 1949 “in recognition of his contributions to the humanist cause and his performance as a Unitarian minister”. He helped create the Fellowship of Religious Humanists, primarily an association of Unitarian ministers, and established the journal, Religious Humanism. In 1978 he received the Unitarian Universalist award for distinguished service. And after returning to live in Salt Lake City in his later years Ed helped us to organize a Humanists of Utah chapter of the American Humanist Association, right here in Zion. Ed was 94 when he died. Can I make a case for saying humanism is good for ones health? In any event, I am most appreciative, despite my distressing first encounter with Ed, for his contribution to my life and to countless other humanists throughout his long and illustrious lifetime.

A little further on in Tom’s sermon he quoted a 1925 statement by Eustace Haydon, then a humanist professor at the University of Chicago and later the leader of the Ethical Culture Society in Chicago. The Haydon item that Tom quoted as reported in William Schultz’s book, Making the Manifesto, read thus:

“Through science man will become master of the earth and rise to undreamed heights. Science…will release the potentialities of every soul…In the new world the production of sick souls will no longer be possible…Purpose will be given to life. The old tragedies, the ancient evils will pass away.”

Hayden clearly over reached in these dated sentiments which almost sound like a parody today such was his moment of excessive exuberance for the advance of science. However, there was a footnote in the back of Bill Schultz’s book related to that quote which read:

In fairness to Haydon, he also called for stricter controls over the uses of science, saying, “The humanist recognizes that science in the hands of selfish men, allowed to create a civilization without the blessing or control of social idealism, has given us the modern age with its cruel maladjustments and its perversion of all human values”…

Bill Schultz also continued in that footnote:

He also disparaged uncritical visions [and again quoting Hayden] “Idealism is sobered by knowledge. Utopias are outmoded. There is no longer a search for panaceas…There will always be problems and new forms of evil.”

The footnote stands in decided contrast to the original quote both Schultz and Tom cited and I would contend these latter sentiments still have relevance today.

If Tom wanted to quote from that era I might have preferred a short sentence of Walter Lippman’s who wrote in his classic work, A Preface to Morals, in 1929: “When men can no longer be theists, they must, if they are civilized, become humanists.”

Following Tom’s quotation of Haydon’s I was really startled to hear him say, “I have not heard humanism offer much different in the last 60 years”. The obvious suggestion was that whatever original thinking might have been done by humanists had ceased 60 to 70 years ago and was now passe. My own experience has been so very different! As a minister and later teacher, psychologist and therapist both my life and professional practice have been greatly enriched through the years by humanistic psychologists such as Rollo May, Erich Fromm, Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, Albert Ellis, James Bugental, Alan Watts and Irvin Yalom. Within our Unitarian Universalist tradition I have been inspired not only by the early humanists writers, Curtis Reese, William Diedrich, Ed Wilson, and Lester Mondale but also in more recent years by Khoren Arisian, Mason Olds, William Schultz, and numerous other humanist ministers and writers whose work has been published in the UU World, in the journal of the Fellowship of Religious Humanists, and other similar publications. In the wider world of humanist thought I have found continuing intellectual stimulation and provocative insights in the writings of such persons as that feisty philosopher from England, Bertrand Russell; Harvard’s scientist par excellence, twice Pulitzer prize winning author, and in the words of one commentator “towering figure in modern science,” Edward O. Wilson; the Renaissance man and author of approximately 500 books (the exact number is in dispute), Isaac Asimov; the unforgettable astronomer, author and TV figure who knew a lot about pursuing mysteries of the universe, Carl Sagan; the tireless promoter of humanism and civil rights and the author of the classic Philosophy of Humanism, Corliss Lamont; and a host of other writers including Gerald Larue and Paul Kurtz whose writings have often been published in the pages of the American Humanists Association’s magazine, The Humanist , as well as The Council for Secular Humanism’s magazine, Free Inquiry. I have also been delving recently into the publications emanating from The North American Committee for Humanism and the Humanist Institute which grapple in a significant way with contemporary social and philosophical issues. Tom said he has set aside his American Humanists Association card. I think that by so doing he may have deprived himself of some vital and relevant material through the years that would have even further enriched his voluminous reading. Indeed, my problem has never been in exhausting enlightening humanist writings relevant to each successive decade but rather to find the time for all the reading I would like to do whether humanistically oriented or otherwise. I should have the T-shirt which reads, “So many books, so little time!”

In Tom’s sermon I was also surprised to hear him extol “mystery,” a concept he said was “frightening to humanists” but essential to our well being. And he offered an esoteric redefinition of the word. I find myself not frightened but decidedly mystified. What we are dealing with at this point is something called epistemology which is a branch of philosophy that deals with, in dictionary verbiage, “the study or a theory of the nature and grounds of knowledge especially with reference to its limits and validity”. In other words, how do we really know what we think we know and how valid is our belief system? We routinely say, “I know…” something or other when deeper analysis often reveals that we are deluded, misinformed, misperceiving or misinterpreting information from our senses. Both unconscious drives and conscious biases muddy the waters and make our supposed knowledge decidedly questionable. Think of the widely divergent witness reports of accidents and faulty reports of crime scenes, the supposed white van sightings in the sniper shootings back East as a much publicized recent example. In the bird watching realm we often say facetiously, “I wouldn’t have seen it if I hadn’t believed it”. Knowing anything with certainty is really very complex though we blithely take our assumptions for granted. In truth, or more appropriately, I think that all we believe and claim we know is based on an element of faith in the veracity of our senses and the validity of our thinking processes, not in spite of or contrary to reason, but based on assumptions that we can not ultimately prove with absolute certainty. In overly extolling reason in the past humanists as well as theists and others have forgotten the inherent faith assumptions upon which we live and move and carry out our everyday existence. That ought to keep everyone humble! We can not ultimately prove that love is better than hate, justice better than injustice, beauty better than ugliness, etc., however obvious such values may seem to us. We may have our preferences, beliefs and values that we are willing to pay a high price for even to the point of death. We may point to both history and the present day to show how we think some values promote human welfare better than others and yet ultimate truth and absolute proof forever elude us. This is what prompts some Post Modernists to claim that we can’t really know anything. However, that stance seems ridiculous on its face. Such persons might better remain silent because from their point of view they don’t really know what they are talking about and further, their listeners wouldn’t really know what they were talking about either. In any event, in the existential living of our lives, we all have to make never ending decisions large and small to maintain, preserve and enrich our lives even if we often do so with fingers crossed. We humanists prefer to utilize reasonableness, experience and the scientific method to guide our thinking complemented by the less obviously reason oriented processes of intuition and aesthetic appreciation. At our best we are open to whatever wisdom is available coming down through the ages from the wisdom literature of the Old Testament, Hellenism, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the varying world religions and the multitudinous productions of countless thoughtful persons throughout the world, in every era down to the present.

So where does the notion of mystery fit into all of this? And how are we to be nurtured by the unknowable, by definition? We often stand in awe and wonder at marvels here on our little planet, and as we look outward into the boundless universe and seek to understand and appreciate more and more with an insatiable appetite. But “Mystery” with a capital M eludes me and doesn’t strike a responsive chord as either a source of guidance or inspiration. Tom said that “it is mystery that nourishes the very center of our lives”. For myself, rather, it is the love of my family and friends, the beauty of the earth, the resplendent arts, the ability to move and think and learn and create and dream, and the opportunity to love, to serve and interact with others that nourishes the very center of my life.

I’m going to over generalize and over simplify here for a few moments before concluding. My working assumption is that the geography we grow up in or spend a lot of time in quite naturally influences both our temperaments and our thinking. Tom has spent a significant portion of his life in New England which is rich in both history and intellectual ferment over the last two centuries including those famous proponents of transcendentalism such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Amos Bronson Alcott, William Ellery Channing, and others. Harvard Divinity School, which Tom attended, has for many years enjoyed a well deserved reputation for ministerial training and as a repository for fine scholarship including that of the well known transcendentalist authors. Perhaps here again a dictionary definition, in this case of transcendentalism, is a succinct and helpful contribution to our discussion:

- A philosophy that emphasizes the a priori conditions of knowledge and experience or the unknowable character of ultimate reality or that emphasizes the transcendent as the fundamental reality.

- A philosophy that asserts the primacy of the spiritual and transcendental over the material and empirical.

I think there is a familiar ring here in thinking of Tom’s emphasis on “mystery” and other similar themes in his sermons.

I, on the other hand grew up in the Midwest which I would describe in short hand fashion as meat and potatoes country and I am a meat and potatoes sort of person…or actually semi-vegetarian these days. (It just goes to show that environment isn’t all determinative.) But I might just as well have grown up in Missouri, the “Show Me State” that prides itself on pragmatism and evidence. Indeed, the midwestern segment of our country has reveled in pragmatism and decidedly less esoteric themes than New England. Thoreau could wax eloquently on Whippoorwills, butterflies and other flora and fauna while the poet of the Midwest, Carl Sandburg, later penned such spartan lines focused on such things as:

Chicago

Hog Butcher of the World,

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders

Or his poem entitled, Happiness:

I asked professors who teach the meaning of life to tell me what is happiness.

And I went to famous executives who boss the work of thousands of men.

They all shook their heads and gave me a smile as though I was trying to fool with them.

And then one Sunday afternoon I wandered out along the Desplaines river

And I saw a crowd of Hungarians under the trees with their women and children and a keg of beer and an accordion.

One can easily think of many other examples of the pragmatic/liberal approach to life in the Midwest from the liberalism of such schools as the University of Wisconsin to the well known liberal politicians of both Wisconsin and Minnesota including Humphrey, Mondale, and Wellstone . There were the well known academics such as John Dewey, perhaps America’s best known philosopher and educator, who in the naturalistic tradition developed his philosophy of Pragmatism at the University of Chicago. I think we could even cite NPR’s broadcasts emanating from Minnesota featuring that delightful raconteur,Garrison Keillor and the fictitious inhabitants of Lake Woebegone . Meadville Theological School in Chicago was the spawning ground for many of the early humanist ministers in Unitarianism and thus was very influential in the spread of humanism throughout the Midwest. Again, as a generalization, as the Unitarian movement moved west across the country from its New England roots the more humanistic the tradition became. Many of you may not be aware that the original name of this church was The First Unitarian Society and continued with that name until 1962 when I, for better or worse, initiated the move to rename our organization The First Unitarian Church, a decision much lamented by some humanists in the congregation at the time. The vote at a congregational meeting was 53 in favor and 18 opposed to the name change which I must confess has been a very minor source of ambivalence for me in subsequent years. You see, we humanists are up front about getting rather twitchy about traditional religious terms such as “worship,” “prayer”, “spiritual” and the biggy, “God,” in association with our religious community even as we try to remember our emphasis upon our prized diversity and “deeds, not creeds.” The terms in question carry so much baggage and ambiguity for many of us that they have lost much of their luster and attraction. I took due note of a recent ad for a new Volkswagen Beetle convertible which spoke of its “spiritual” qualities. (That must be some automobile!) Many of us have worked with such diligence to evolve a philosophical position of integrity that we are undoubtedly over sensitive to the persistence of some words in our religious gatherings that have decidedly lost their appeal.

But to move this discussion to a close I would point out the obvious, that my generalizations about New England as contrasted with the Midwest and the thought forms therein are decidedly limited. I thoroughly enjoy reading Thoreau as one of my heroes and Emerson as well, and I imagine Tom could also say a few good words for the likes of Dewey and Sandburg. And I believe that Tom and I, whatever our philosophical differences might be in some particulars, are united on much common ground. I feel confident neither of us expects supernatural assistance in helping us with multitudinous and ever present human dilemmas. Both of us would agree that it is vitally important for each of us to develop a belief system that is satisfying, promotes ones well being, and is congruent with the best information available from whatever source. Both of us would agree that it is essential to keep both head and heart involved in our religious quest. Both of us would be in agreement that our religious beliefs, ethics and practices need to be borne out with diligence in the daily round and in unstinting efforts to create a better world for all of its inhabitants. As Ed Abbey once said, “passion without action is the ruin of the soul.” There are so many challenges facing all of us, personally and collectively, locally and throughout the world, that we must continually renew our vision, tap into our courage, join with others in our efforts, and do what needs to be done as long as we are able. So let us take heart and proceed with high resolve as we pursue those challenges together. And thanks to Tom for offering me this opportunity to share a different point of view.